There has been a lot of discussion of graduate medical education (GME) funding in response to a recent IOM report. Basically, under the current system Medicare wites a blank check to academic training centers based on the number of GME positions they have. An issue not discussed is how institutions allocate GME slots between different training programs. The way training positions are allocated determines the number of primary care physicians and the mix of specialists vs. subspecialists in the physician workforce. Slot allocation is, therefore, a critical issue in healthcare policy.

Changes in GME Slot Allocation

The number of GME training positions has increased only 17% over the past two decades, but there have been significant changes in the allocation of GME slots between primary care and medical specialties and between specialties and subspecialties. The allocation of GME training programs and residents are summarized in Table 1 (data from Brotherton and Etzel 2002, Brotherton and Etzel 2008, and Brotherton and Etzel 2013)

| Programs | Residents | ||||||

| Year | Specialty | Sub- specialty | Total | Specialty | Sub- specialty | Total | % Sub-specialty |

| 1995 | 4356 | 3301 | 7657 | 86299 | 11736 | 98035 | 12.0% |

| 1996 | 4351 | 3436 | 7787 | 86320 | 11756 | 98076 | 12.0% |

| 1997 | 4368 | 3493 | 7861 | 86421 | 11722 | 98143 | 11.9% |

| 1998 | 4331 | 3561 | 7892 | 85631 | 11752 | 97383 | 12.1% |

| 1999 | 4268 | 3678 | 7946 | 85460 | 12529 | 97989 | 12.8% |

| 2000 | 4228 | 3757 | 7985 | 85081 | 11725 | 96806 | 12.1% |

| 2002 | 4176 | 3888 | 8064 | 85368 | 12890 | 98258 | 13.1% |

| 2003 | 4169 | 4023 | 8192 | 86357 | 13607 | 99964 | 13.6% |

| 2004 | 4151 | 4095 | 8246 | 86975 | 14316 | 101291 | 14.1% |

| 2005 | 4149 | 4254 | 8403 | 88241 | 14865 | 103106 | 14.4% |

| 2006 | 4134 | 4368 | 8502 | 89269 | 15610 | 104879 | 14.9% |

| 2007 | 4119 | 4470 | 8589 | 89618 | 16394 | 106012 | 15.5% |

| 2008 | 4100 | 4594 | 8694 | 90907 | 17269 | 108176 | 16.0% |

| 2009 | 4128 | 4745 | 8873 | 91963 | 17877 | 109840 | 16.3% |

| 2010 | 4131 | 4836 | 8967 | 93153 | 18433 | 111586 | 16.5% |

| 2011 | 4152 | 4959 | 9111 | 94486 | 18941 | 113427 | 16.7% |

| 2012 | 4207 | 5180 | 9387 | 94990 | 20121 | 115111 | 17.5% |

| 1995 to 2012 | -3% | 57% | 23% | 10% | 71% | 17% | |

The number of specialty programs has decreased form 1995 to 2012, but the number of subspecialty programs has increased by 57%. The total number of residents has increased 17% over this time period with a 10% growth in the number of specialty residents and a 57% increase in the number of subspecialty residents. As a percentage of the total, the fraction of GME slots devoted to subspecialty training has increased from 12.0% in 1995 to 17.5% in 2013. Similar results are reported by Wynn et al

Looking more closely at recent data, in specialty training programs, from 2008 to 2012 the total number of positions increased by 6.4% while the fraction of slots devoted to primary care specialties has increased by 3.5%. Despite repeated calls for increasing the number of primary care physicians over the past several decades, the fraction of GME training slots devoted to training primary care physicians has actually fallen from 36.6% in 2008 to 35.6% in 2012.

| 2008 | 2012 | Change | |

| Family med | 9353 | 9934 | 6.2% |

| Internal med | 22132 | 22710 | 2.6% |

| Pediatrics | 8089 | 8332 | 3.0% |

| Total primary care | 39574 | 40976 | 3.5% |

| % primary care | 36.6% | 35.6% | |

| Pathology | 2312 | 2282 | -1.3% |

| Radiology | 4455 | 4438 | -0.4% |

| Surgery general | 7712 | 7828 | 1.5% |

| Orthopedic surgery | 3303 | 3501 | 6.0% |

| OB/Gyn | 4815 | 4931 | 2.4% |

| Anesthesiology | 5208 | 5507 | 5.7% |

| Emergency medicine | 4750 | 5458 | 14.9% |

| Cardiology | 2589 | 2718 | 5.0% |

| Interventional cardiology | 240 | 300 | 25.0% |

| Hematology/ Oncology | 1393 | 1531 | 9.9% |

| GI | 1292 | 1407 | 8.9% |

| Dermatology | 1069 | 1191 | 11.4% |

| Opthalmology | 1220 | 1343 | 10.1% |

| Total | 108176 | 115111 | 6.4% |

Large increases are seen in some subspecialties including emergency medicine, interventional cardiology, dermatology and ophthalmology. Non direct patient care specialties including pathology and radiology have seen an absolute decrease in resident positions and most surgical specialties have not kept pace with the overall growth in the number of residency positions.

The Resident Cap

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA) fixed the number of medical residents that would be funded by Medicare indirect medical education (IME) and direct graduate medical education (DGME) reimbursement at the number for each hospital in 1996. The cap was modified in 1997 to exclude consideration of podiatry and dental residents, and in 1999 the Balanced Budget Refinement Act (BBRA) increased the limit for rural teaching hospitals to equal 130% of each rural teaching hospital’s 1996 resident count (source AAMC).

From 2002 to 2012, there has been a gradual increase in the total number of GME training positions. This may be the result of funding from sources other than Medicare, or institutions funding additional slots with internal resources. It also reflects a shift toward fellowship training which is partially supported by the institution and partially funded by Medicare or Medicaid.

Direct Financial Impact of GME Programs

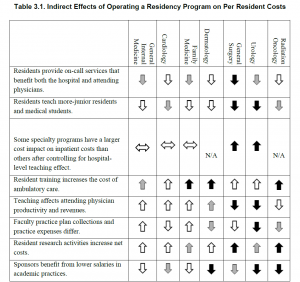

The financial impact of GME programs has been examined recently (Wynn et al., 2013). Table 3-1 from their work is reproduced below.

Direct financial costs/savings may be part of the reason primary care training positions have not kept pace with overall growth in training positions. Primary care training programs are a burden on faculty time in outpatient clinics and residents do relatively little to save the institution money. On the other hand, these direct costs do not explain the lack of growth in surgical programs and predict that dermatology would shrink rather than showing the dramatic expansion that has been observed.

Indirect Financial Impact of GME Programs

It is difficult to study individual programs or medical specialties in isolation. For example, hospital and specialty clinics generated $7.23 of charges for every $1 of charges in primary care (Saultz et al., 2001). The rapid growth in emergency medicine programs may reflect these indirect financial impacts. Emergency rooms (ER) are literally the gateway to most hospitals with many centers moving to a model where all admissions are processed through the ER. ERs not only generate significant revenue themselves, they are also key drivers of revenue across the institution.

Marketing and Advertising

As noted by Wynn et al, having GME training programs enhances an institution’s reputation, and essentially all of the top ranked hospitals nationally have GME training programs in a wide range of specialties and subspecialties. Priorities in marketing may explain some of the changes that have occurred in GME slot allocation.

Reward for Faculty/Departmental Contributions to the Institution

In an academic center, training slots are an important currency for faculty recruiting and retention. Faculty are motivated by their desire to be involved in training and in many cases forgo significant personal income as a result of their decision to pursue an academic career. It follows that the size of a training program is a key consideration for faculty in choosing between institutions. Further, both department size and training program size correlate strongly with national rankings across a wide range of academic disciplines. A reasonable hypothesis is that hospital administration award training grant slots in part to reward faculty and departments that are benefitting the institution.

Admissions

In the past, the number of available GME training slots exceeded the number of US medical graduates and many GME slots, particularly in primary care specialties, went unfilled. With the growth in MD, DO and offshore medical degree programs, the number of medical graduates now significantly exceeds the number of available GME training slots and essentially all positions are filled. Programs may once have been unwilling to expand primary care training programs because they could not fill their existing programs. High applicant demand may still motivate expansion of some training programs, but lack of demand is no longer a major issue.

Conclusions

The need for an increase in the number of primary care physicians has been widely discussed for several decades. Despite widespread agreement that healthcare would benefit from increased numbers of primary care physicians, the absolute number of GME training slots devoted to primary care specialties has not kept pace with the increase in total number GME training positions. The proportion of positions dedicated to training subspecialists has increased with notable growth in interventional cardiology, emergency medicine, dermatology and ophthalmology. The subspecialties that have increased disproportionately are all hospital based or make extensive use of hospital resources and all generate substantial financial returns for hospitals.

While non-patient contact specialties like radiology and pathology are hospital intensive, these services do not generate demand. Rather they provide services requested by other physicians. With improvements in imaging and analytic technology, the productivity of physicians in these non-patient contact specialties has likely improved meaning that hospitals do not need to expand these programs to meet demand.

The changes in GME slot allocation appear to reflect the needs of hospitals rather than the needs of the broader community. Shifting the distribution of training slots to better address the needs of the community and Medicare/Medicaid system could improve the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the healthcare system.

Brotherton, S. E., and Etzel, S. I., “Graduate Medical Education, 2011–2012,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 308, No. 21, pp. 2264–2279.

Brotherton, S. E., and Etzel, S. I., “Graduate Medical Education, 2008–2009,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 306, No. 9, 2009, pp. 1015–1030.

Brotherton, S. E., Simon, F. A. and Etzel, S. I., “Graduate Medical Education, 2000–2001,”Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 286, No. 9, 2001, pp. 1056–1060.

Saultz, J. W., McCarty, G., Cox, B., Labby, D., Williams, R., and Fields, S. A., “Indirect Institutional Revenue Generated from an Academic Primary Care Clinical Network,” Family Medicine, Vol. 33, No. 9, 2001, pp. 668–671.

Wynn, B. O., R. Smalley, and K. Cordasco. 2013. Does it cost more to train residents or to replace them? A look at the costs and benefits of operating graduate medical education programs. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR324 (accessed October 14).